While much of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 was focused on individual and corporate tax reform and simplification, one of the biggest new planning opportunities that emerged was the creation of a new 20% tax deduction for “Qualified Business Income” (QBI) of a pass-through entity, intended to provide a tax boon to small businesses that would leave more profits with the business to help it grow and hire.

The caveat, however, is that the QBI deduction was only intended to provide tax benefits for profitable businesses that hire employees, not to provide tax benefits for high-income professions who generate their profits directly from their own personal labors. As a result, the new IRC Section 199A created a so-called “Specified Service Business” classification that, at higher income levels, would not be eligible for the QBI deduction.

The challenge, however, is that the exact definition of what constitutes a “Specified Service Trade or Business” (SSTB) has not always clear, given the wide range of professional services that exist in the marketplace. In addition, as soon as the rules themselves were released, creative tax planners began to strategize about how to arrange (or re-arrange) revenue and profits to maximize the amount of income eligible for the QBI deduction and minimize exposure to the Specified Service Business rules.

In this guest post, Jeffrey Levine of BluePrint Wealth Alliance, and our Director of Advisor Education for Kitces.com, examines the latest IRS Proposed Regulations for Section 199A, which provides both important clarity to how the “Specified Service Business” test will apply in various industries, including rather broadly for professions like health, law, and accounting, but only narrowly to high-profile celebrities who may have their endorsements and paid appearances treated as specified service income but not the income from their other businesses that may still materially benefit from their high-profile reputation.

Of greater significance for many small business owners, though, are new rules that will force businesses with even just modest specified service income to treat the entire entity as an SSTB, limit the ability of specified service businesses to “carve off” their non-SSTB income into a separate entity, and in many cases aggregate together multiple commonly owned SSTB and non-SSTB business for tax purposes.

Ultimately, the new rules are only impactful for the subset of small business owners who engage in specified service business activities and have enough taxable income to exceed the thresholds where the phaseout of the QBI deduction begins (which is $157,500 for individuals and $315,000 for married couples). Nonetheless, for that subset of high-income business owners, effective planning to avoid having SSTBs “taint” non-SSTB income, or to split off non-SSTB income to the extent possible, will be more challenging than before.

Jeffrey Levine, CPA/PFS, CFP, AIF, CWS, MSA is the Lead Financial Planning Nerd for Kitces.com, a leading online resource for financial planning professionals, and also serves as the Chief Planning Officer for Buckingham Strategic Wealth. In 2020, Jeffrey was named to Investment Advisor Magazine’s IA25, as one of the top 25 voices to turn to during uncertain times. Also in 2020, Jeffrey was named by Financial Advisor Magazine as a Young Advisor to Watch. Jeffrey is a recipient of the Standing Ovation award, presented by the AICPA Financial Planning Division for “exemplary professional achievement in personal financial planning services.” He was also named to the 2017 class of 40 Under 40 by InvestmentNews, which recognizes “accomplishment, contribution to the financial advice industry, leadership and promise for the future.” Jeffrey is the Creator and Program Leader for Savvy IRA Planning®, as well as the Co-Creator and Co-Program Leader for Savvy Tax Planning®, both offered through Horsesmouth, LLC. He is a regular contributor to Forbes.com, as well as numerous industry publications, and is commonly sought after by journalists for his insights. You can follow Jeff on Twitter @CPAPlanner.

On August 8, 2018, the IRS released the much-anticipated proposed regulations for IRC Section 199A. The regulations provide a veritable treasure-trove of information, and in particular, clear up many of the questions surrounding Specified Service Trade or Businesses (SSTB). Most importantly, they provide much-needed clarity to determine exactly what businesses should be classified as an SSTB (or not). This determination is of minimal importance to low and moderate income earners (up to $315,000 for married couples filing joint returns, and up to $157,500 for all other filers), but is critical to high earners above those thresholds, who may see their qualified business income (QBI) deductions related to specified service trade or businesses partially or fully phased out as their income exceeds those thresholds.

The primary purpose of the IRC Section 199A deduction for Qualified Business Income (QBI) was to provide a tax boon for businesses that hire and employ people to grow the US economy, but not to give a deduction to those who simply earned a substantial income from the fruits of their own labor. Not that all service businesses would be prohibited… just specifically the ones that generated income primarily by providing various types of professional services.

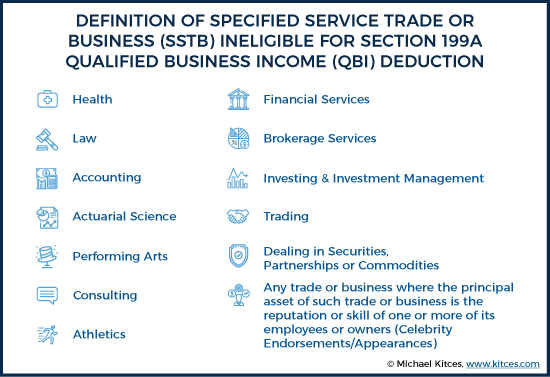

Accordingly, IRC Section 199A defines certain “Specified Service Trade or Businesses” (SSTBs) that, at higher income levels, are not eligible for the QBI deduction. Drawing on IRC Section 1202(e)(3)(A) (which defines eligibility for certain types of small business stock capital gains to be excluded from income, and similarly is not available for professional services firms), the legislative text of IRC Section 199A stipulated that an SSTB would include:

“…any trade or business involving the performance of services in the fields of health, law, accounting, actuarial science, performing arts, consulting, athletics, financial services, brokerage services, or any trade or business where the principal asset of such trade or business is the reputation or skill of 1 or more of its employees.”

(Notably, IRC Section 1202(e)(3)(A) also includes engineers and architects, but those professions were explicitly excluded from the list of SSTB professions under IRC Section 199A(d)(2)(A).)

In addition to the businesses listed above, IRC Section 199A(d)(2)(B) adds the following businesses to the list of SSTBs:

“…any trade or business which involves the performance of services that consist of investing and investment management, trading, or dealing in securities.”

While some of these professions are relatively straightforward to define, the original legislative text for Section 199A left much up to interpretation when determining whether or not certain businesses would be treated as a specified service trade or business (SSTB), both with respect to certain edge cases within professions (e.g., does an accountant who only does tax preparation but not business accounting and auditing still “count” as accounting services, and does income from selling insurance products count as “financial services” or only providing investment advice?), and the relatively broad catch-all at the end of the SSTB list for “any trade or business where the principal asset of such trade or business is the reputation or skill of 1 or more of its employees” (raising the question of whether a restaurant qualifies for the QBI deduction, but a restaurant with a star chef might not?).

Fortunately, the new IRC Section 199A regulations provide a great deal of clarity about where, exactly, to draw the line between the 13 different types of specified service businesses and all other types of service businesses.

Some types of SSTBs are relatively straightforward and required minimal clarification from the IRS, such as athletics and performing arts. The regulations do, however, clarify that persons engaged in supporting services, such as those who maintain or operate equipment or facilities for such businesses, are not SSTBs, themselves.

Determining what types of and roles within various professional service occupations fall into – and just as important, do not fall into – the other SSTB categories was less clear from the original legislation, though, and thus required more specific guidance from the IRS in the regulations.

Given that the healthcare sector is now the largest employer in the US economy, “Health” services was one area where there were a number of open questions about the scope of the specified service rules. For instance, while it’s relatively straightforward that doctors are in the health profession… it was less clear whether pharmacists and similar ‘related’ healthcare professionals would be included in the definition, as well as veterinarians and others providing “healthcare” to non-humans. The proposed regulations take an inclusive approach here and make clear that both pharmacists and veterinarians are considered health services, and thus, are SSTBs. Accordingly, the newly proposed regulations stipulate that:

“…the performance of services in the field of health means the provision of medical services by individuals such as physicians, pharmacists, nurses, dentists, veterinarians, physical therapists, psychologists and other similar healthcare professionals performing services in their capacity as such who provide medical services directly to a patient (service recipient).”

The proposed regulations also take a similarly inclusive approach with respect to the fields of “accounting” and “law.” As a result, the former includes not only “accountants,” but also “enrolled agents, return preparers, financial auditors, and similar professionals,” while the latter also includes “paralegals, legal arbitrators, mediators, and similar professionals” in addition to lawyers, themselves.

Of particular importance to financial professionals, five of the 13categories of SSTBs directly relate to various professions within the financial industry (financial services, brokerage services, investing and investment management, trading and dealing in securities, partnerships or commodities), while two more could relate indirectly (consulting and the “principal asset is the skill or reputation of one or more employees”). Thus, many high-income owners of financial services businesses will be considered owners of an SSTB and will begin to see their QBI deduction phase out once their income exceeds their applicable threshold.

Some of the financial services professions explicitly “called out” in the proposed regulations as unequivocally being SSTBs include “financial advisors, investment bankers, wealth planners, and retirement advisors," as well as those “receiving fees for investing, asset management, or investment management services, including providing advice with respect to buying and selling investments.” Businesses engaged in either the trading or dealing of securities, commodities, or partnership interests are also SSTBs, as are brokers of securities (i.e., registered representatives of a broker-dealer).

While most financial services professionals are engaged in SSTBs, the regulations do exclude real estate agents and brokers from the definition of an SSTB as well. More importantly, though, the regulations also grant two other very notable exceptions to the rule: traditional bankers (not investment bankers), and insurance agents or brokers. Is this simply because they have better lobbyists than the rest of the financial industry? Perhaps that played at least some role, but the crux of the issue can be traced back to the initial legislative text creating the QBI deduction.

As noted earlier, under IRC Section 199A(d)(2)(A), an SSTB is any business described in IRC Section 1202(e)(3)(A), other than engineers and architects (who apparently also have very good lobbyists!), including:

“…any trade or business involving the performance of services in the fields of health, law, accounting, actuarial science, performing arts, consulting, athletics, financial services, brokerage services, or any trade or business where the principal asset of such trade or business is the reputation or skill of 1 or more of its employees.”

Conspicuously absent from the list of businesses above are banking and insurance. Notably, these businesses are included in the following subparagraph of the IRC, IRC Section 1202(e)(3)(B), which states:

“any banking, insurance, financing, leasing, investing, or similar business”

However, when Congress wrote the law defining what constitutes an SSTB, it explicitly stated only the professions under IRC Section 1202(e)(3)(A) – and not IRC Section 1202(e)(3)(B) – would count. Accordingly, the IRS determined in its proposed regulations that a more narrow interpretation of “financial services” (one that does not include traditional banking or insurance services) was appropriate. After all, if Congress wanted to include those businesses in the definition of SSTBs, they could have referenced both IRC Section 1202(e)(3)(A) and IRC Section 1202(e)(3)(B) when it created IRC Section 199A. Its failure to do so provided the IRS with enough legislative intent that they explicitly excluded those businesses from the definition of an SSTB in the regulations.

As a result of the difference between the way qualified business income from financial planning/securities brokerage/investment advice is treated as compared to qualified business income from insurance services, many registered investment advisors and/or securities brokers who also conduct insurance business will find that the profits from their different businesses will be treated markedly different from one another. While profits from the financial planning/securities brokerage/investment advice business(es) will be potentially ineligible for the QBI deduction once the owner’s taxable income exceeds $207,500, or $415,000 if married and filing a joint return, profits from the insurance business may still eligible for the deduction as a non-SSTB (though calculating the deduction would still involve analyzing the W-2 wages paid by the insurance business, as well as any depreciable property owned by the business, under the separate wage-and-property test for the QBI deduction).

Unfortunately, though, it is not uncommon for certain advisors, particularly solo-advisors, to run both their brokerage/advisory revenue and their insurance revenue through the same “financial advisor” sole-proprietorship. In the past, this often made sense, as treating the brokerage/advisory business as a separate business from the insurance-related business would generally lead to unnecessary complication and expense, both from the requirement to keep two sets of books, as well as the need to file multiple Form Schedule Cs (or other business returns) with the advisor’s personal income tax return.

Now, however, in light of the proposed regulations’ differentiation between the profits of the two businesses, high-income advisors may wish to more clearly separate and delineate these different “lines of business” into two, distinct businesses. If not, the proposed regulations’ de minimis rule, discussed in greater depth below, could “taint” any insurance services profits that would otherwise be eligible for the QBI deduction.

When the legislative text for IRC Section 199A was created, one of the most nebulous aspects of the definition of an SSTB was the catch-all provision that, “any trade or business where the principal asset of such trade or business is the reputation or skill of 1 or more of its employees,” is an SSTB. How would the IRS determine whether an employee or business owner's “skill or reputation” was the driving force behind the business’s profits? Rightfully so, many practitioners were concerned that this language could ensnare just about any business with a successful and high-profile founder/owner.

For example, “Jan’s Furniture Shop” probably doesn’t fall into the category of an SSTB. But what if Jan was highly regarded as the most skilled furniture maker in town, and her reputation as a skilled craftsman was what drove sales? Exactly how skilled or respected would Jan have to be before the business crossed over from a non-SSTB to an SSTB? Similarly, “Bob’s Diner” probably isn’t an SSTB, but what if “Bob” was actually famous chef Bobby Flay? Clearly, such an analysis is highly subjective at best, which was a primary driver of many practitioners’ concerns.

Thankfully, these concerns are no longer necessary. In what was a relatively surprising move, the IRS defined the meaning of a trade or business where the principal asset of that business is the reputation or skill of one or more employees or owners in, perhaps, the narrowest of possible ways.

According to the proposed regulations, a business is only considered an SSTB by virtue of the “reputation or skill” provision if, and only if, it generates fees, compensation, or other income via one or more of the following:

As a result of the IRS’s extremely narrow interpretation of the “reputation or skill” provision in the 199A regulations, the provision has gone from potentially being one of the primary culprits of classifying a business as an SSTB, to being fairly benign, and applicable only to an extremely limited number of “businesses” that are truly built around “celebrity” endorsements, appearances, and the like.

In fact, the proposed regulations include a number of IRS-provided examples, and Example 8 of Section 199A-5(b)(3) of the regulations provide perhaps the best insight as to how narrowly the IRS has framed this “reputation or skill” provision.

H is a well-known chef and the sole owner of multiple restaurants, each of which is owned in a disregarded entity. Due to H’s skill and reputation as a chef, H receives an endorsement fee of $500,000 for the use of H’s name on a line of cooking utensils and cookware. H is in the trade or business of being a chef, and owning restaurants and such trade or business is not an SSTB. However, H is also in the trade or business of receiving endorsement income. H’s trade or business consisting of the receipt of the endorsement fee for H’s skill and/or reputation is an SSTB within the meaning of paragraphs (b)(1)(xiii) and (b)(2)(xiv) of this section.

If the chef in the example above is able to receive an endorsement fee of $500,000 for the use of their name on a line of cooking utensils and cookware, it’s probably pretty safe to assume that they are not only a pretty good chef (i.e., they are skilled) but that they are also fairly well known (i.e., has a strong reputation). As such, two of the primary drivers of the chef’s restaurants revenues are likely the chef’s skill and reputation. And yet, in the example, the IRS makes clear that these restaurants would not be considered SSTBs, as they do not meet the (favorably) rigid definition of the “reputation or skill” provision outlined above, despite the fact that they are likely successful at least in material part to the “reputation or skill” of their celebrity chef-owner.

Many businesses engage in more than one specific activity or business line at a time, creating a potential challenge to determine whether or not the business, as a whole, is an SSTB. In some cases, this is ostensibly easier because the business lines are literally separated into discreet separate entities, for liability protection and/or other purposes (even though they’re still “related” entities). Though in the extreme, separating businesses into discrete entities also creates the concerning potential (at least for the IRS) that firms will carve off what otherwise would have been SSTB profits (not eligible for the QBI deduction) into separate entities that would qualify (even though in the aggregate it shouldn’t have).

Accordingly, the proposed regulations provide guidance on how to deal with both circumstances, both with respect to determining when the SSTB revenue in an otherwise non-SSTB business must be treated as such, and when and whether to aggregate back together separate-but-related SSTB and non-SSTB entities into one SSTB.

Oftentimes, a single business will simultaneously conduct multiple business activities. In some situations, one or more of those discrete activities, if conducted by a separate business, would cause that business to be treated as an SSTB. The proposed regulations do not, as some had hoped, allow a single business to separately account for different lines of revenue and expenses and segregate SSTB profits vs. non-SSTB profits. Instead, the entire business is either an SSTB… or it’s not. As such, either all of the profits of a business are profits of an SSTB entity, or all of the profits are profits of a non-SSTB.

This raises an obvious question… how much revenue can a single business generate from an activity that would be considered an SSTB if conducted in its own, separate business, before the entire business is considered an SSTB? The answer, unfortunately, is “not much."

Under the proposed regulations, if a business has gross revenue of $25 million or less during a taxable year, then the business must keep its SSTB-related revenues to less than 10% of its gross revenue to avoid SSTB status. Or conversely, the $25M-or-less-revenue business will be considered an SSTB if just 10% or more of its gross revenue is derived from an SSTB-type activity!

In the event a business generates more than $25 million of revenue during a taxable year, the SSTB rules are even more restrictive. Such businesses will be considered an SSTB if just 5% or more of their gross revenue is derived from an SSTB-related activity.

Example #1: Frank is an optometrist, and is the sole owner of Spectacular Spectacles, LLC, which is primarily engaged in the manufacturing and sale of eyeglasses (not an SSTB-related activity). Occasionally, however, Frank will perform (and charge for) eye examinations, in part, to determine a customer’s correct prescription. These exams are related to health services, and thus, are an SSTB-related activity.

In 2018, Spectacular Spectacles, LLC generates $3 million of gross revenue. The $3 million of gross revenue is comprised of $2,880,000 million of revenue related to the manufacturing and sales of eyeglasses, with the remaining $120,000 of revenue attributable to Frank’s occasional vision exams. Since just 4% ($120,000 / $3 million = 4%) of Spectacular Spectacles, LLC’s total revenue is comprised of SSTB-related revenue, the business will not be considered an SSTB.

There are a number of interesting corollaries to the SSTB de minimis rule. Most notable is the fact that although it’s business’s profits that are eligible for the QBI deduction in the first place, the determination of whether or not a business with revenue from multiple activities is considered an SSTB is determined solely by the ratio of its revenue from SSTB activities in relation to its total revenue. Which is concerning, because it means a high-revenue low-margin specified service business can taint the QBI deduction for an entire high-profit non-SSTB!

Example #2: Bill, one of Spectacular Spectacles, LLC’s employees, decides to leave and start his own eyeglass manufacturing and sales company, Glasses for the Masses, LLC. Bill is not a doctor, but in an effort to drive business and compete with his former employer, he hires several optometrists who can perform vision examinations and heavily promotes and advertises this service.

In 2018, Glasses for the Masses, LLC generates $1.6 million of revenue and $550,000 of profits. As a result of the profits, Bill is over his applicable threshold, and thus, will be ineligible for any QBI deduction if his business is deemed an SSTB.

Analyzing Glasses for the Masses, LLC’s revenue and profits further, it is determined that $400,000 of the company’s total revenue is derived from the heavily marketed eye examinations. However, after accounting for expenses, including the salaries of the two optometrists, this activity only generates $50,000 of profit. In contrast, the core business of manufacturing and selling eyeglasses generates $1.2 million of revenue, and $500,000 of profit.

Only about 9% ($50,000 /$550,000 = 9.09%) of Glasses for the Masses, LLCs profits are attributable to an SSTB-related activity. The entire business, however, and all of the profits, will be considered an SSTB for 2018 since 25% ($400,000 / $1.6 million = 25%) of its revenues are attributable to the SSTB-related optometry activity… well more than the 10%-of-revenue hurdle necessary to wind up with that categorization. The end result? Bill gets $0 of QBI deduction on his $550,000 of profit (almost all of which was non-SSTB profit, but all of which was disqualified as a high-income SSTB business nonetheless!).

For business owners like Bill, there are a couple of different options.

One option, for instance, would be to simply eliminate the SSTB-related activity that’s not all that profitable in the first place. Unfortunately, that may be easier said than done. What if much of Glasses for the Masses, LLC’s revenue and profits from the manufacturing and sale of glasses (non-SSTB-related) is due to the fact that customers are able to get an eye examination and purchase their eyeglasses in one location (which, in the extreme, could make it worthwhile to keep the SSTB service that disqualifies the QBI deduction simply because it’s “necessary” for the business)?

Another option for business owners like Bill is to split the various activities into legitimate, bona fide, separate businesses. In such situations, each business will generally be evaluated on its own merits. Splitting activities into separate businesses in this manner (e.g. creating GM Optometry to perform optometry services) might create some operational challenges for Bill, such as the need for customers getting an eye exam and purchasing glasses to pay two separate bills to the two separate companies (an eye exam bill to the optometry business and a glasses bill to Glasses for the Masses, LLC), but the resulting tax benefits may be worth it. In Bill’s case, it would mean a 20% tax deduction on up to $500,000 of profits… annually!

On the other hand, the proposed regulations do have an additional layer of rules specifically intended to limit splitting off a multitude of small non-SSTBs to insulate them from an SSTB core (which wouldn’t be applicable in the example above, but could be an issue for an optometrist that primarily provided eye exams as health services and just sold a few eyeglasses “on the side”). Specifically, under the “incidental-to-SSTB” rules, if a non-SSTB has 50%-or-more common ownership with an SSTB and has shared expenses, it must have revenues of more than 5% of the combined revenues of both businesses, or they will all be aggregated as an SSTB anyway. Accordingly, in order to be treated as a separate SSTB (and not taint the non-SSTB core), the separate business must either have revenues of more than 5% of the combined entities, or have its own entirely independent cost structure and not share wages, overhead, or other business expenses.

Example #3: Jerry, Spectacular Spectacles, LLC’s most popular optometrist, decides to go out on his own as an optometrist, and over 3 years quickly grows to generate $500,000/year of revenue. While Jerry’s business is solely focused on providing optometry (health services), which is an SSTB, his wife Elaine (an artist) suggests that he start selling a small number of designer eyeglasses (with her art designs).

After 2 more years, Jerry’s optometry practice grows to $600,000/year in revenue, and his wife’s separate eyeglass business (sold in Jerry’s medical offices) generates $15,000 of revenue. Normally, an eyeglasses business is not an SSTB, but because Elaine’s eyeglass business is under common ownership with Jerry’s optometry business (via the shared attribution rules for married couples), and they share expenses (since she uses Jerry’s office space to sell her glasses), and the eyeglass revenue is only 2.4% of the combined $15,000 + $600,000 = $615,000 revenue, any profits on Elaine’s eyeglass business will be treated as SSTB income (phasing out their QBI deduction altogether given Jerry’s high income).

Further complicating the matter is the fact that a business conducting both SSTB-related and non-SSTB-related activities may periodically change from an SSTB to a non-SSTB (or vice versa), and back again, depending upon the ratio of SSTB-related revenue to total revenue each year.

This is possible because, under the proposed regulations, the de minimis rule states that:

“For a trade or business with gross receipts of $25 million dollars or less for the taxable year, a trade or business is not an SSTB if less than 10 percent of the gross receipts of the trade or business are attributable to [an SSTB]”. (emphasis added)

The key point is that the proposed regulations’ stipulate that the de minimis rule is applied separately “each taxable year.” As a result, the determination of whether a business conducting both SSTB-related and non-SSTB-related activities is itself an SSTB is an annual test, based on whether the SSTB-related revenue is more than 10% (or in the case of >$25M revenue businesses, more than 5%) in each year!

The 80/50 “Spin-off Killer” Rule (A.K.A. The Anti- “Crack and Pack”)

Almost immediately after the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act’s creation of IRC Section 199A, practitioners went to work dissecting the new section and coming up with creative ways to allow clients to claim greater deductions.

One of the most widely discussed strategies for high-income business owners was something that came to be known as the “crack and pack.” In short, the “crack and pack” was simply the idea of spinning off certain elements of an SSTB – often business-owned real estate - into a separate, commonly-owned entity, in order to shift income from an SSTB (for which a QBI deduction on profits may have been phased out) to a non-SSTB (for which a QBI deduction on profits may still be available).

Unfortunately, the proposed regulations put a severe wrinkle – if not a death knell – in the “crack and pack,” thanks to the new “80/50 rule” outlined in Section 199A-5(c)(2) of the regulations.

Under this provision, if a “non-SSTB” has 50% or more common ownership with an SSTB, and the “non-SSTB” provides 80% or more of its property or services to the SSTB, the “non-SSTB” will, by regulation, be treated as part of the SSTB.

Example #4: Betty is a doctor, and is the sole owner of her practice, which is organized as an LLC. The net income from her practice – which falls under the “health” services category of the SSTB definition – is $800,000 per year. As a result, Betty cannot claim a QBI deduction. Betty’s LLC also owns the medical office out of which she practices, having purchased it several years ago for $2,000,000.

Prior to the issuance of the proposed regulations, one strategy Betty might have contemplated with her tax planner was spinning the medical office out into a separate LLC, or other business structure, and having the medical practice pay rent to the rental business for its use of the property. Prevailing wisdom was that while the profits of the medical practice would have been ineligible for the QBI deduction, the profits from at least the new (now-separate) rental business would have eligible for at least a partial QBI deduction (effectively converting that portion of the income from SSTB to non-SSTB income).

The proposed regulations make clear that such a series of transactions would now be fruitless. Assuming that Betty’s medical practice continued to use 100% of the office space after it was spun out into a new entity, she would be in “violation” of the “80” part of the 80/50 rule, since more than 80% of the non-SSTB’s property would be used by a SSTB. Similarly, assuming she was the owner of the business into which the medical office was transferred, she would be in violation of the “50” part of the 80/50 rule, since the common ownership between the SSTB and the non-SSTB would be 100%! Thus, the rental business and its income would, by rule, still be treated as an SSTB.

The “best” way to “beat” the 80/50 rule will often be to “attack” the “50” part of the rule by trying to get the common ownership between the SSTB and the non-SSTB business entities below 50%. Once the common ownership (which includes both direct and indirect ownership by related parties) between the two entities is less than 50%, the anti-“crack and pack” rules don’t apply, and the non-SSTB will actually be treated as a non-SSTB!

Notably, trying to avoid the 80/50 rule by simply ensuring the SSTB business uses less than 80% of the non-SSTB’s property and services (e.g., by buying the entire medical office complex, renting out the other suites, and using just a small portion of the office space for the commonly owned medical practice) will only be of limited effectiveness. The reason is that, under the rules, if a “non-SSTB” is providing less than 80% of its services/property to a 50%-or-greater commonly-owned SSTB, a portion of the business’s profits will still be considered part of an SSTB! In such situations, the portion of the business’s services/property that is not provided to the commonly-owned SSTB will not be treated as an SSTB, but the portion of business’s services/property that is provided by commonly-owned SSTB will still be treated as an SSTB!

Example #5: Kanwe Beatum, LLC, is a law firm, and thus, an SSTB. The owners of the firm have recently decided to purchase a large office building in a separate (but commonly owned) entity, Fancy Offices, LLC, of which 40% will be rented to Kanwe Beatum at fair market value to conduct future operations, while the other 60% will be rented to unrelated businesses.

Here, only 40% of the non-SSTB Fancy Offices property (the building) will be provided to the SSTB law firm (which is lower than the 80% threshold). The ownership, however, between Kanwe Beatum, LLC and the Fancy Offices entity in which the office building is purchased is identical (≥50%). As a result, 40% of Fancy Offices will be treated as an SSTB (i.e., 40% of its revenue and profits will be subject to the SSTB phaseout tests), while the remaining 60% will not.

Ultimately, the “good” news of the new SSTB rules is that they still only apply to a limited subset of small business owners – those that do engage in at least some level of “specified services”, and have income that is high enough to exceed the thresholds ($157,500 for individuals and $315,000 for married couples) where the QBI phaseout kicks in. Nonetheless, for high-income small business owners who do meet those thresholds and have specified service income, careful planning will be more important than ever to avoid running afoul of the new rules, especially with respect to trying to separate (and avoid “tainting”) non-SSTB income from the less-tax-favored income of specified service businesses.